At an end-of-school party with other Grade 1 parents at my daughters’ school in June, I was struck by how anxious other parents were about approaches to teaching and learning that focus on play, curiosity, collaboration, and inquiry. Many parents want their children to be schooled in academic fundamentals and for them to excel at reading, writing, and performance. But too much emphasis on schooling, particularly when children are young, foregoes opportunities to practice approaches to learning that enable children to learn over their lifetimes. Over the summer, I’ve been reading about creativity and I came across a wonderful memoir and scholarly argument for social and creative learning with technology.

Mitchel Resnick’s Lifelong Kindergarten makes for worthwhile back-to-school reading for parents wanting to better understand why we should support learners to cultivate curiosity, passion and skills through playful, creative projects relevant and meaningful to learners themselves.

“I am convinced the kindergarten-style learning is exactly what’s needed to help people of all ages develop the creative capacities needed to thrive in today’s rapidly changing society.” (p.7)

Resnick’s perspective on creativity and learning is individual, social and constructivist in comparison to the radical socio-cultural view I explored in my last post about the work of Reijo Miettinen. Lifelong Kindergarten is in part a history of Resnick’s research agenda at the MIT Media Lab and community interventions through the Computer Clubhouse Network. The book unpacks the key principles of learning that inform Resnick’s work: projects, passions, peers, and play. Although much of Resnick’s work focuses on fostering creativity for children and youth through technology, he demonstrates that principles equally apply in adult and higher education. Below, I share some compelling ideas from the book for parents.

Wider Walls and Lower Ceilings

Resnick shares an accessible set of educational principles that teachers and parents can use to think about learning, drawing on the work of Seymour Papert. Places of learning offer:

- “easy ways for novices to get started (low floors)”

- “ways for them to work on increasingly sophisticated projects over time (high ceilings)

- “support and suggest a wide range of different types of projects, and multiple pathways” (wide walls) (p.139)

Although Resnick equates wider walls with accommodating different learning styles, a problematic concept that parents and educators should reject, I agree with his point that learning must tap into the passions and interests of individual learners and that the aims of learning must be facilitated and negotiated by learners and their educators.

Offer Examples but Throw Away the Instructions

Resnick views teachers as facilitators of learning. He argues learners should be offered examples of different kinds of projects that are possible rather than detailed sets of instructions. Ultimately, the learner should have agency to decide whether or not to participate.

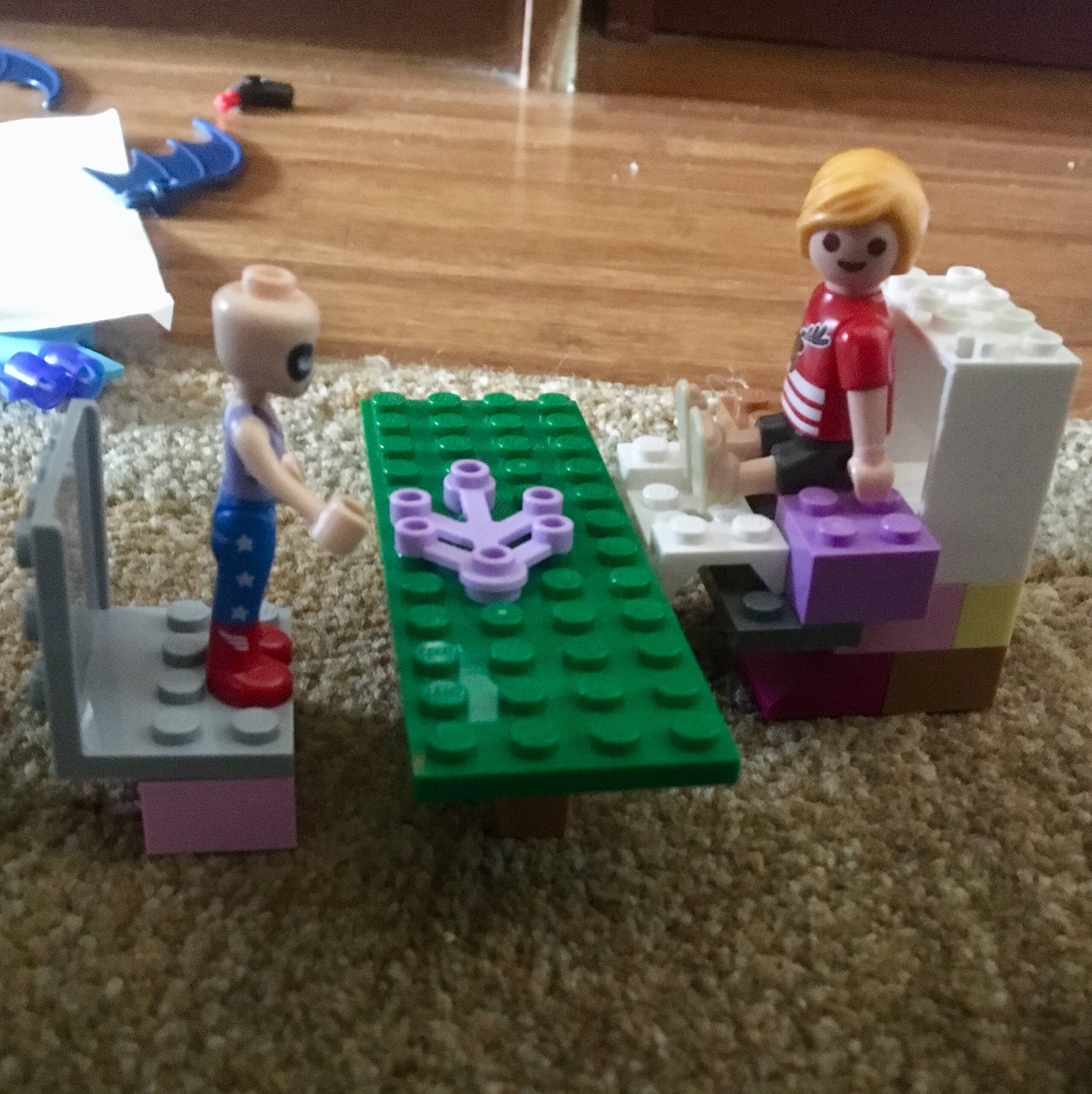

For example, Resnick suggests than children should aim to use LEGO to build their own creations rather than to build the thing shipped in the box. I decided to test out his approach and asked my daughters to use Lego to share the highlight of their day camp at the Aquarium during the summer holidays. Claire chose to represent a squid dissection:

This open-ended project approach is appealing in light of the teleological, closed approach of following the instructions to build a figure in the box or prescribed teacher-assigned exercises with right answers.

I witnessed an excellent example of how to embrace toys as a creative medium at “The Art of the Brick”, a special exhibit at the Canadian Museum of Science and Technology in OttAwa featuring the work of Nathan Sawaya. Sawaya’s art was demonstrated the flexibility of LEGO bricks as an , particularly his multimedia collaboration with Australian photographer Dean West.

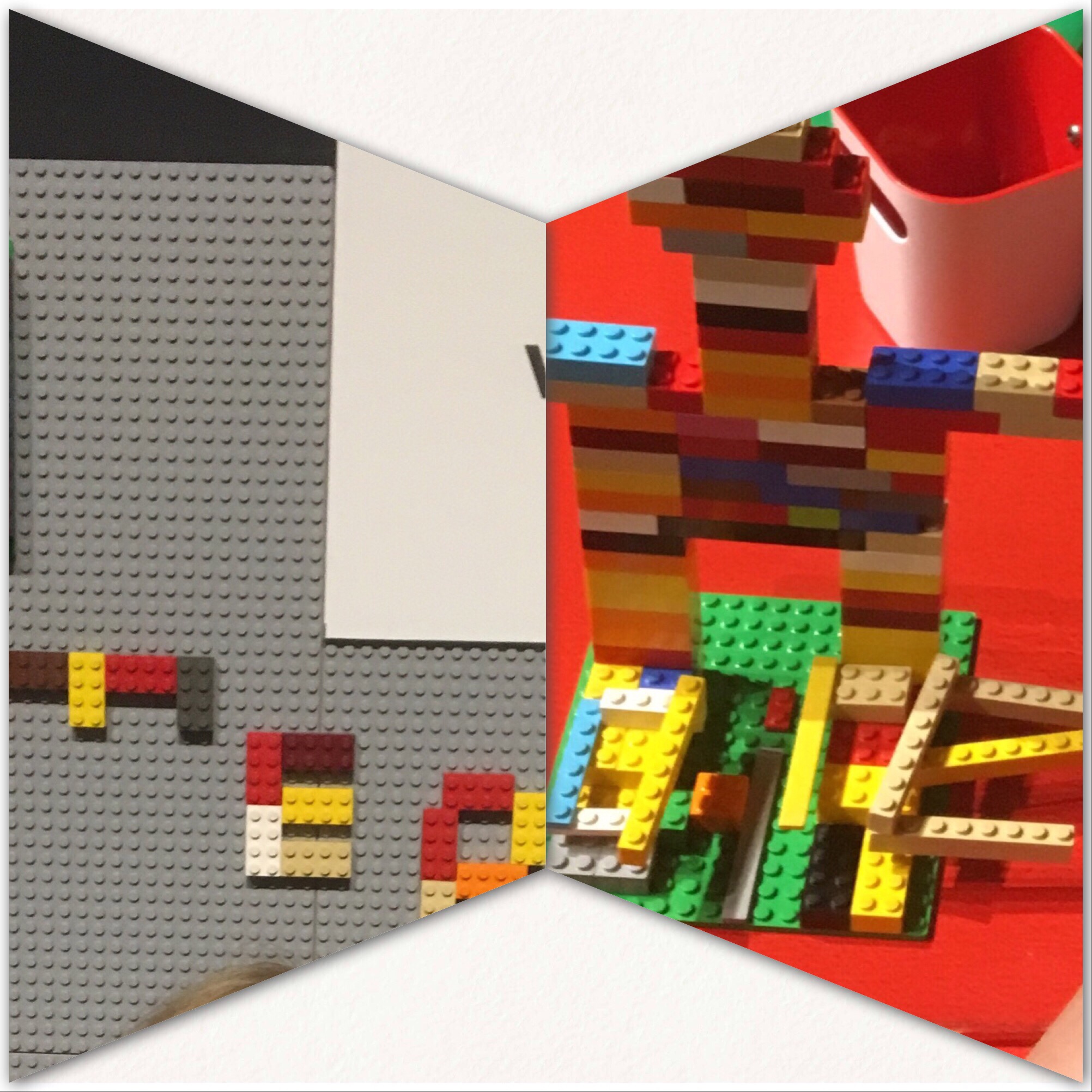

The most powerful part of the exhibition was the learning space at the end where inspired visitors were allowed to take up a set of challenges. The space featured a range of age-appropriate challenges and examples to inspire the builders. Claire and Megan took up the challenges each in their own way.

Let them tinker and play

“Tinkerers understand how to improvise, adapt, and iterate, so they are never hung up on old plans as new situations arise. Tinkering breeds creativity.” (p.136)

Empowering others to create begins by letting them tinker and learn through experience and error. Calls to let people learn through tinkering with materials and task is as old as apprenticeship, yet in the last 20 years, we have witnessed the democratization of making and and doing. There is the rise of the Maker Movement, design thinking, and Lego Serious Play.

Tinkering is at the root of prototyping and artistic endeavors. People must represent concepts through sketches and prototypes before they can make them a reality. Tinkering is at the core of agile business methodologies. I think people are predisposed to tinkering. My brother is a tinkerer with mechanical things. I am a tinkerer with ingredients. Maybe the point is that we each have our preferred material to tinker with. Malfoudis, in How Things Shape the Mind, argues that cognition is the dynamic interaction between mind, material and social context, so the meaning of a child’s LEGO creation is inextricable interwoven with the socio-cultural history of the blocks, and the socio-cultural context in which the assemblage is happening including the stimulus that is near by and the facilitate knowledge and guidance by the others who are in the space.

Resnick’s chapter on play is a highlight of Lifelong Kindergarten because it also make the argument that children vary in how the approach learning tasks. He summarizes academic studies of play. Resnick cites Harold Gardner’s distinction that some children approach play as drama and others approach play as a challenge of finding patterns. This is not some either-or psychological binary, and I suspect that a given person’s approach will vary depending on the task, but Resnick makes the point that learning environments are likely set up to privilege one approach over the other, and, as a result, put one part of the population at a disadvantage. This is one reason why innovative approaches to K-12 education, like British Columbia’s new curriculum, which empowers teachers to combine aspects of education more easily to address a limited number of intended learning outcomes, creates opportunities for more children to achieve the results expected of them by making it easier for embedding serious learning in playful work.